Bangladesh and other apparel sourcing countries have made significant progress in the apparel value chain in the last few decades. However, social up-gradation remains weak in the supplying countries. A study conducted by Dr Khondaker G Moazzem and Kishore K Basak of Centre for Policy Dialogue have found that weak institutional structure of the judicial system in the supplying countries makes it difficult to resolve social issues in the value chain including workers’ wages, workplace safety and security and worker’s rights. The study suggested that the ‘external’ governance of the value chain can be considered to be a possible avenue to facilitate social compliance where buyers would play the lead role.

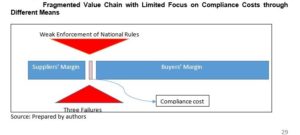

The study said that the market mechanism has some role to play in poor compliance records of some supplying countries. “A consistent rise in sourcing of apparels from major supplying countries despite having poor compliance records indicate that compliance standards at the factory level has been compromised which may directly and indirectly benefit major players in the supply chain,” the study said.

It suggested that necessary costs for maintaining compliances are supposed to be built-in the margin of the suppliers and therefore distribution of margin both at the suppliers’ and buyers’ end is likely to have limited implications on maintaining compliance.

The study pointed out that in a state of fierce competition, low cost for compliance is practiced by market players as a strategic tool in order to maintain competitiveness and thereby ensuring higher profit.

The study refers a previous study by Ahmed & Nathan (2014) in which it was showed that the FOB price for the main apparel export items of Bangladesh is around 11 per cent of the retail price. This indicates that the buyers and retailers earn high margins and also a rent from wage arbitrage (difference in wages in destination and manufacturing countries.

Compliance in Bangladesh’s apparel sully chain

During the pre-Rana Plaza period, firms usually maintained physical and social compliances taking into account the national rules as well as the guideline followed by buyers/brands/retailers under their code of conduct. During the post-Rana Plaza period, the apparel sector has undergone major restructuring on compliance related issues. A number of private sector initiatives including Accord, Alliance and ILO supported initiatives are in force to oversee the compliance standard at the factory level. As part of those initiatives a new guideline for fire and electrical safety and physical integrity has been prepared. Compared to the guideline followed during pre-Rana plaza period, this guideline is quite comprehensive regarding physical compliance. A detailed list of important compliance related aspects of the guideline is presented in Annex 1.These standards have been set based on the national rules and regulations as well as international rules and regulations where national rules are inadequate. Most of the firms are moderately equipped with major physical compliance related indicators such as fire-fighting system and other equipment including fire alarm and signs. However, sprinkler and smoke/heat detector systems are not available in most of the sample firms. Majority of the factories follow national regulation of having one toilet for every 25 workers. But there are concerns regarding other compliance issues such as width and number of stairs, dining facility, pure drinking water facility and lighting and ventilation.

Social Compliance

In the study, sample firms were asked to score their social compliance including minimum wage, identity card, participation committee, service-book for workers, no use of forced labour and child labour, discrimination and harassment and timely payment of wages etc. Majority of indicators are found to be in better state in the sample firms including ensuring minimum wage, ID card for every worker, workers’ participation committee, service-book for the workers, discrimination/harassment in the workplace, forced and child labour (Table 4). However, there are issues such as timely payment of wages, forming workers’ welfare committee, having proper day care centre for workers’ children which need further improvement. Better compliance is found in most of the factories in case of minimum wage, identity card, participation committee, service book for workers, no forced and child labour and no discriminatory treatment. Moderate level of compliance standard is found in case of no harassment and abuse, payment of wage at right time and facilities for taking leaves. Overall, level of compliance on social issues is better compared to that of physical issues.

There is no major difference between different categories of firms in terms of maintaining social compliance. Most of the social compliance related indicators are found ranked better in all categories of factories. Minor differences are observed in the case of timely payment of wages, incidents of harassment and abuse and getting weekly leaves. Since a large part of these issues have been enforced since early 2000s, no major difference is observed at this stage. Overall, social compliance standard has been maintained as per the CoC of the buyers which is mainly due to the result of long practice of those standards at the firm level.

Costs for Maintaining Compliances at Firm Level

Maintaining compliance in the factories requires investment of different kinds. A part of those investments are project related fixed cost mainly for setting up physical compliance. A part of the investment is met up from working capital which is of variable cost in nature, mainly related with social compliance and partly with physical compliance. These fixed and variable cost of firms are supposed to be met from the margin received by the suppliers. The level of compliance maintained at the factory depends on firms’ investment for maintaining physical and social compliance. The cost for compliance is usually shown under heads of selling, general and administrative (SGA) cost and overhead cost of manufacturing. Firms of all kinds are not spending equally on compliance enforcement. In fact large and directly contracting firms spend more on compliance. It is important to examine how profit held by small firms affects the costs that are required for maintaining compliance. Overall spending on compliance and level of compliance at the firm level is likely to be closely associated.

Margin for Suppliers in Other Countries

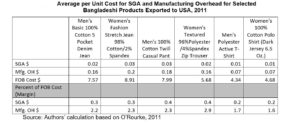

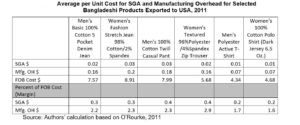

Bangladesh’s higher expenditure on fabric, trimming and packaging needs to be examined closely- whether it is related to lack of capacity of domestic textiles industries to supply fabric at low price or it is related to higher import cost and associated lead time for import of fabric from nearby sources including India and China? Interestingly, Bangladeshi manufacturers invariably spend less for SGA and manufacturing overhead compared to major competing countries for all major exported products to USA. In fact, these expenses comprise the lowest share in overall cost structure.

The differences of costs are rather high between Bangladesh and other major supplying countries for a number of items including labour costs, manufacturing overhead costs, selling and general and administration (SGA). The highest level of difference is observed in case of SGA (between 50-400 per cent) followed by labour costs (between 35-300 per cent) and manufacturing overhead costs (between 30-75 per cent) (Table 9). Better spending on compliance is likely to provide benefit in terms of profit to firms of major supplying countries. Differences of fabric related costs indicate that Vietnam and China spent about 1 to 5 per cent less compared to that of Bangladesh while other countries such as Mexico, Honduras and Nicaragua spent about 9 to 14 per cent more.

Compliance and competitiveness

Bangladeshi firms need to investment more for compliance. However, rise of compliance related expenses is not easy for the suppliers as it may reduce the competitiveness of Bangladeshi products vis-à-vis those of other countries. For example, average costs of Mfg OH and SGA for men’s basic 100% cotton 5 pocket denim jeans of the selected eight countries is US$2.5 and US$0.7 respectively. If Bangladesh needs to increase compliance related costs at par with those average costs, it needs to increase both the costs by US$0.4 each which would cause a rise in total FOB costs by about 19 per cent and 57 per cent respectively. Such rise of costs for compliance would increase overall FOB cost of the product from the existing level of US$7.57 to US$7.63 which could make Bangladeshi products costlier compared to that of other countries such as Vietnam. An alternative of this is to accommodate those additional costs by cutting suppliers’ profit margin; this would not be so easy in low-level of profit margin. Thus a straight rise of compliance related costs by Bangladeshi suppliers without necessary adjustment in other costs may not be feasible.

A possible alternative could be improve the level of cost efficiency in major cost components such as costs for fabric and trimming and packaging. As discussed earlier, Bangladesh is relatively cost inefficient in those two items particularly against those of China and Vietnam. Bangladesh’s average fabric costs for selected items was US$3.90 in 2011 which was US$0.18 higher than that of China and US$0.05 higher than that of Vietnam.

Despite high spending on compliance, firms of major competing countries enable to maintain their competitiveness through other means. There are many economic and non-economic factors that play important role for better competitiveness (Table 12). Major economic factors include low interest rate, low operating costs, higher productivity, low wastage, higher efficiency of labour, skilled labour force and low cost of raw materials etc. Without sufficient improvement in those factors, it would be very difficult for Bangladeshi manufacturers to increase spending for compliance under the existing level of margin.

- a) Addressing Market Failure:

There needs to be an integrated value chain in the apparels sector where market players will jointly share responsibility in the whole value chain. In this context, a well- functioning mechanism needs to be set up in the whole supply chain which could ensure effective enforcement of compliance at the work place at the suppliers’ end. Shared responsibility between suppliers and buyers and respective governments and other multilateral agencies needs to be ensured in order to improve compliance at the suppliers’ end.

- b) Addressing Coordination Failure: The social audit initiative of the buyers need to be well coordinated with that of national audit. Buyers auditing mechanism is not functioning properly. The buyers/brands/retailers while providing orders to suppliers are supposed to take into account that necessary compliance are maintained.

- c) Addressing Information Failure: Although a number of international guidelines on responsible business practice of the MNEs/buyers are available which particularly focus on workers’ rights, workplace safety and security, implementation of those guidelines is rather weak. A major challenge is failure to get adequate information about buyers’ business practices in the supplying countries with regard to compliance related issues.

Margin for Buyers

It is very difficult to get a detailed breakdown of margin distributed among all the market agents in the apparel value chain. A major challenge was that most of the data highlight margins on the supplier’s side as opposed to the retailers’/buyer’s side, limiting the narrative of the research. The Fair Wear Foundation and several other publications by labour rights organizations including the Clean Clothes Campaign were used to determine the margins of individual parties in the value chain. The Fair Wear Foundation (FWF) (2013) made an analysis on breakdown of margin of a €29 T-shirt sold in the European market. The major parties in the value chain include the manufacturers, the wholesalers and the retailers each receiving about 17 per cent, 24 per cent and 59 per cent of retail price, respectively (Table 14). A similar study was carried out by Swiss bank J. Safra Sarasin (2014) in case of product sold in the US market and yielded similar results. Table 14 below summarizes information from the two sources. According to Rehman Sobhan (2014), the margin distributed at suppliers’ end was about 28 per cent while the rest 72 per cent is distributed at the buyers’ end. The margin received by suppliers include cost for fabric/yarn (about 15 per cent of retail value of products), administrative and overhead costs (8 per cent), and operating profit (5 per cent). Mustafizur Rahman (2014) in an informal discussion has mentioned about such wide difference in the distribution of margin between major market players. Overall, the large share of total margin is distributed at the buyers’ end which need to be discussed from market based analytical perspective.

Investing in superior information technology systems will eliminate many problems. Retailers can automate parts of the business and integrate business functions to improve operations efficiency and effectiveness (Booz & Company 2010). The industry’s fragmented nature and low switching costs could mean “savvy technology usage can become real competitive differentiators, while also significantly lowering the retailer’s cost-to-serve (Booz & Company 2010). Investing in technology has more benefits such as helping to reduce – the amount of retailer margin eroded by theft, waste and virtually training employees (Sivara, Miller and Meany 2005).Unfortunately, many retailers still rely on legacy systems that are difficult to maintain and hamper integration of the supply chain. Upgrading IT systems are very expensive but retailers must make the investment to stay competitive. Overall market operations at the buyers/retailers’ end is quite different with that of suppliers’ end and market forces are different and they acted differently. Thus a disjointed value chain is in operation in the apparels sector of Bangladesh where existing structure and market forces put little emphasis on compliance.

Recommendations

The study suggested the following recommendations. First, the allocation for maintaining compliance by apparel firms needs to be increased as part of this additional spending could come from higher CM. Second, the component of compliance related expenses need to be made separate in the cost structure of the suppliers as well as of the buyers/retailers. There should be appropriate mechanism under which spending on compliance could be monitored transparently. Third, suppliers should take necessary measures to generate additional resources in order to spend on compliance by further reducing production cost by improving productivity and efficiency. The attitude towards lowering the spending for compliance in order to increase the return needs to be avoided. Fourth, the institutional mechanism to monitor and inspect the factory level compliance needs to be ensured. The government should allocate more resources for enhancing the capacity of respective organizations as well as take initiatives to strengthen their governance practices. Fifth, the social audit system practiced by the buyers/retailers need to be strengthened; as part of it, different players including occupational health and safety committee, national and international NGOs, working on social issues need to be integrated in the auditing process. Sixth, strengthening international rules, norms and guidelines are also necessary with a view to better regulate the buyers/brands and retailers to maintain compliance at the factory level. Seventh, all kinds of market agents who are engaged in sourcing of apparels from supplying countries need to be registered under proper authority and have to follow international guideline and be monitored properly.

The sustainability of the apparels value chain depends not only on economic upgrading but also on social upgrading. The challenge is to maintain a balance between these two kinds of upgrading and thereby to ensure competitiveness in the global market. This is true both for suppliers and buyers. Based on the study it can be suggested that along with strengthening the institutional mechanism, both suppliers and buyers have to take responsibility towards ensuring compliance in the production process.

The article is based on the study “Margin and Its Relation with Firm Level Compliance Illustration on Bangladesh Apparel Value Chain” carried out by Centre for Policy Dialogue in collaboration with Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES), Dhaka. Dr Khondaker G Moazzem and Kishore K Basak were the authors of the study.

CPD RMG Study Stitching a better future for Bangladesh

CPD RMG Study Stitching a better future for Bangladesh